0 Comments

It helps to know if a drive to the store is going to take 12 minutes or 2 hours as I am trying to schedule my errands for the week.

Likewise, when planning on working through a learning module, task, or activity it helps to know how long (about) it will take to complete. The dedication to "time on task" is easier to make when I, as a learner, know how much time is going to be required. Like my trip to the store, it will have a big influence on how I plan my time and how I prepare myself. This is why I add an estimated time to complete (ETTC) to actionable items in my courses. I have found that ETTC helps learners overcome their procrastinations by eliminating some of the ambiguity of what time a commitment to action entails. Considering the messy schedules they often have to navigate, its useful for to know if they can squeeze a chapter reading in before their meeting that starts in 30 minutes. If they don't know that it only takes 10-15 minutes (on average) to read the chapter, they likely will not even bother. ETTC enables them to pace and schedule their engagement effectively. In addition, an ETTC provides them with a measure to compare their own time on task to. If it is taking a hour to complete something that should take 10-15 minutes this would be a red flag that something is amiss. Did I mention that ETTC should be a range? It should be a range. Because you are bad at estimating. If you know the time to complete then its just TTC. Which is fine too. We've seen a commitment to communicating time to complete work well elsewhere; from cooking recipes to time stamps on videos. ETTC is useful information for making a decision about when or whether to engage with something. Its also useful to know that this recipe should only take 20-30 minutes, but I'm on day two, something is wrong. I'm not going to spend another two days making Pasta de Pepe but I will watch an informative 3 minute video. Time is a cost and learners want to know how much they are paying. note1: ETTC helps schedule, pace, prepare, compare

postscript1: Don't get too macro with your ETTCs. Try to provide an ETTC to each actionable item. postscript2: Use learner feedback to improve your ETTCs.

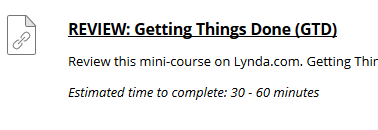

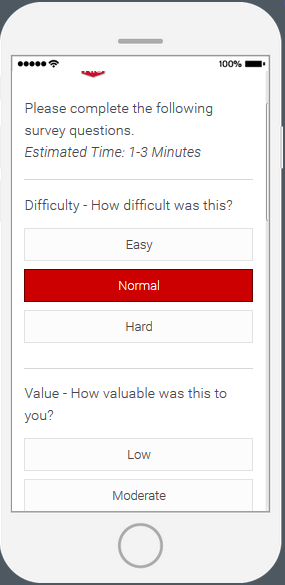

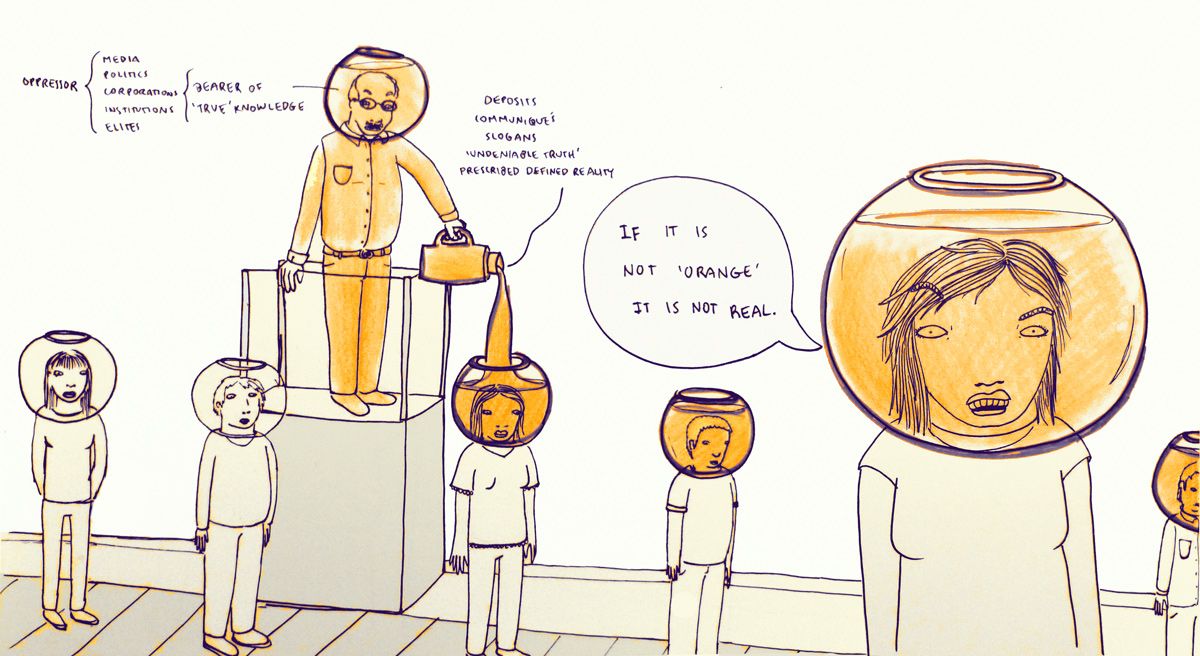

DifficultyEasy - Normal - Hard The difficulty scale reports learners' perception of personal challenge or required skill to meet the target's requirement. ValueLow - Moderate - High The value scale reports learners' perception of usefulness that the target provided them in exchange for their time and efforts. EngagementLow - Moderate - High The engagement scale reports learners' perception of attention, motivation, and interest toward the target. EffortLow - Moderate - High The effort scale reports learners' perceptions of their personal commitment toward the target. Effort is a hedge against the other indicators - which reflect more on design and not external motivators. Timedd:hh:mm - modifiable Learners' report of the time spent on task, or exposure to the target. OpinionOptional essay or short answer Opinion is optional written feedback. Can be a qualitative summary, highlights, lowlights, suggestions to improve, etc. USES I've used the information from this survey in two ways: (1) to provide formative feedback that allows me to be responsive to learner cohorts: do they need more remedial instruction? are they taking too long on the readings? did they enjoy this activity? These are elements that I can use to tune instruction in motion: add more activities like this, divide the remaining readings, post remedial content, etc. (2) To provide summative feedback that will inform the next design versions. If 80% of my students thought the readings were too hard, maybe it's time to reevaluate or replace the text, or provide additional support. I can also track the feedback throughout the course and across student groups. There are several useful insights that this simple instrument can yield. Learners may report that an activity was difficult, but very engaging and valuable; or that an assignment was valuable, but it took too long and wasn't engaging. This might encourage the development of like activities, or spur the redesign of an assignment, respectively. Importantly, it also gives learners the opportunity to provide direct feedback on what might be improved (or what exactly was so great) through the opinion field - so they can tell you exactly what you did wrong and you can fix it. LEARNER REFLECTION I've found that this tool also helps learners to reflect on their experiences, even if briefly. This is especially useful if DVEETO is used with mid-level experiences like online modules or multi-tiered assignments or activities, since they have to recall their experiences and own sense of commitment (effort) in sum to provide a response. Since reflection tends to be good for long-term retention, this tool can be a cheap and easy way to promote it. LIMITATIONS This is not a research-grade instrument. It's not meant to be. It's intended to provide useful feedback for course development and instruction that learners will actually complete. It allows me to compare what my design expectations were against their real experiences and make informed changes. I would not use this to justify grand declarations about how a particular course element improved student learning outcomes. The number of possible responses is intentionally limited (3) and I advise against adding more options. More options take longer and require more thinking. Long, reflective thinking is fine for end-of-course/training surveys. That's not what this is for. No one wants to spend 10 minutes on a survey covering a 5 minute video. That said, you may want to modify the questions. MODIFICATIONS As-is, this tool may not be for you. I am working primarily in a higher-education environment teaching undergraduates and training faculty. So you may find that you don't need some of these fields or that there is one that is missing that would be useful to you and your context. I think these are fairly universal, but all six questions are not always necessary. In fact, I actually recommend dropping as may questions as you can - but no more then you can't. If you are using the survey on the above-mentioned 5 minute video, do you really need to know how long your learners spent on it? I'm going to guess it was about 5 minutes. Again, this isn't some rigorously tested research instrument, so mix-and-match at your discretion. Just don't make it an hour long because no one is going to take the time to complete it, unless you make them, and then they will hate you and your dumb survey. WHAT ABOUT ASSESSMENT? What about it? This is not an assessment tool, its a feedback tool. You aren't going to use it to find out if learners actually learned the content. That's a separate issue. However, it can be attached to items such as tests or assignments to inform you of learners perceptions of them. It would be interesting if say, your learners report that a test was easy but end up failing miserably. There is probably something there for you to fix. Its also worth noting that assessment by itself is not the best way to judge the effectiveness of your instructional design. Learners may simply be highly motivated to get through your awful course because they really, really want to be a doctor, or engineer, or to be in compliance with your company's new policy, or so their parents don't take away their video games. Don't be fooled that performance alone is necessarily a good indicator of effective design. Ask your learners.  Alfie Kohn is one of my favorite contemporary educators. For the past 6 years he has challenged my conceptions about the purpose of education and the practice of teaching, particularly in relation to EdTech. After reading his recent post I found almost all of my sentiments mirrored in his commentary. I've highlighted a few key quotes below with some additional thoughts. "Despite corporate-style declarations about the benefits of “innovation” and “disruption,” new forms of technology in the classroom mesh quite comfortably with an old-school model that consists of pouring a bunch o’ facts into empty receptacles." As in many technology-related fields, the terms 'innovation' and 'disruption' are used ad nauseam in EdTech circles. Although I am a younger practitioner, I have already become cynical about the use of technology for education. Partially because every new product is labeled as some kind of 'game-changer.' In most cases, these 'innovations' do little more than help us do the wrong things more efficiently, more often, and in more places. I am reminded of the banking model of education, but for the 21st Century. Even the late Jerry Bracey never imagined things could get this bad when he referred to how we were developing the capability “to do in nanoseconds things that we shouldn’t be doing at all.” Imagine an accounting firm that needed help fixing a complex spreadsheet formula and workflow issues. Now, imagine that the popular solution to this problem setting up a virtual reality (VR) simulation of the accounting office where employees can log into from home using their company provided Oculus Rift. The VR program allows them to interact naturally with the digital office environment using motion capture technology and eye tracking. They can even use a recreation of their computer to complete their accounting tasks using the same spreadsheet that used at work. It integrates with the existing 'real life' systems and even updates in real time! Obviously we haven't fixed the problem. Nor has the situation been improved by cutting-edge technology. All we have done is to create yet another iterative platform from which the same erroneous practices and systemic problems can be expressed. Yet, this seems to be the type of approach we take to solving pedagogical problems using EdTech. Just look back to how iPads were going to "change everything" in 2010-12. All we have done is to create yet another iterative platform from which the same erroneous practices and systemic problems can be expressed. These are shiny things that distract us from rethinking our approach to learning and reassure us that we’re already being innovative. Consumerism is surely the pervasive ideology in American culture, and education professionals are infrequently exempt from its draw. The illusion of progress is everywhere: virtual reality, 3D printers, home-delivery drones, smartphone apps that analyze our bowel movements and recommend dietary changes, billboards that read information from our smartphones and provide us with an unsolicited, highly personalized advertisement. Things are getting better! Innovation! There are certainly more advancements in technology - but is access getting better? Do we really think that schools which can't afford air conditioning systems are going to be able to outfit every student with a virtual reality headset? Perhaps all we are doing is creating a new technological apartheid between the haves and the have-nots. Even for those who are blessed with cutting edge technologies, they unfortunately aren't using them to liberate learning. In the case of the iPad, it became little more than a battery-powered replacement for was already being used by teachers - the medium has changed but the message has stayed the same. These 'shiny things' give us hope for the future, but not a means to attain it. In the end, the technology becomes little more than a status symbol. the medium has changed but the message has stayed the same. Show me something that helps kids create, design, produce, construct — and I’m on board. Show me something that helps them make things collaboratively (rather than just on their own), and I’m even more interested Kohn goes on to distinguish two terms and concepts in regard to more 'individualized' learning: Personalized Learning: involves adjusting the difficulty level of prefabricated skills-based exercises based on students’ test scores Personal Learning: involves working with each student to create projects of intellectual discovery that reflect his or her unique needs and interests The former concept continues to perpetuate the problem of treating students as clay to be molded, rather than autonomous individuals with agency. It continues to baffle me that in spite of all of the external demands for a diverse and critically thinking labor force that we figure the best way to achieve that goal is to create flexible systems which aims to ensure that every student learns and achieves exactly the same things at the same time according to the same standards. This isn't what we know is right about human learning. It seems to be about about reinforcing a process and means of assessment that provides nice little graphs for administrators and legislators to justify their decisions - "We can't create adaptive learners, so lets create adaptive learning systems!" Unsurprisingly, the latter concept I am a bigger fan of. The moral approach here is to treat human beings as human beings, not as data points, not as problems to be solved. These are people with unique backgrounds and skill sets, different needs, wants, desires, and interests. We should embrace that diversity, not work to extinguish it. Personal learning also addresses our '21st century*' labor needs which rightfully include the ability to do REAL problem solving, to think critically, and to work collaboratively. It avoids the problem of a massive workforce with little diversity in skill at a time when we need increased diversity in skill to address the mounting problems here in the United States and the world at large. This isn't to say that I think education is about workforce training, but I do think is has a clear relationship to it. While I will not argue that there are basic, fundamental skills that every student should know, I will say its a much, much shorter list than currently exists - and much more meaningful under the personal learning paradigm. We should be outfitting our students with technology to encourage them embark on their own learning paths. Not using it to coerce them into the crumbling infrastructure of last century's education models. I can use a pen to write great literature, or I can use it to stab someone in the arm. Technology is a tool to be used for good or for ill, it depends on us to make its decisions. For every EdTech project that we take on the future we need to ask how it will help liberate student learning and avoid recreating our past failures. *21st Century, First World We can't create adaptive learners, so lets create adaptive learning systems! Below is a short essay that I completed at the start of my junior year for a social psychology course. At this point in my life I had no idea that I would end up in academia as a professional educator/trainer. I can start see how little reflections like this throughout my ugrad in psychology led me to where I am. September 15, 2008 Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation in My Education Keeping intrinsic motivation to learn has been a very difficult thing for me to retain throughout my scholastic career. I feel the intense focus on grading has had much to do with this. Why do we lose interest in subjects that once intrigued us? Since I can remember, the start of every academic year has been exhilarating for me. I have a genuine interest in school and always start off very eager to learn. About a month or two in, however, I lose most of that excitement. My motivation shifts from going to class because I enjoy and having a genuine interest in the subject being taught, to going because I may miss something that will be on the upcoming exam. I slowly grow to resent the class. However, there have also been classes that I have enjoyed in [their] entirety and was honestly disappointed when it came time for [them] to end. Even ones that initially didn't catch my interest I found myself wanting to continue on.

What made me like these classes more than others? Why did I enjoy a class that was totally unrelated to my initial interests more than one that was? In retrospect, I have an idea why. The classes that I found held my interest were ones where the instructor had the least amount of focus on grading. Instead they focused more on teaching the material and making the class fun and interesting. Perhaps my favorite class of all time was a Philosophy class on Ethics. The grading in this class was based on 2 factors; 3 tests and 1 paper. No attendance, no participation, no homework. The tests themselves were never hard unless you had completely disregarded the class material and the final paper was on an ethical subject of personal choice. Rain or shine, snow or sleet, I made this class. I was intrinsically motivated to go. Learning for me was fun and intensely satisfying. To this day there have been few classes have had the same effect on me and the ones that have were structured in a similar fashion. In contrast, I am almost always repelled by past math courses. Although I find mathematics very interesting, I normally only make it two or three weeks before my desire to attend class drops to none. The last course I took, for example, I only attended when something important was happening (tests, quizzes, homework due). I had no motivation to make it to class or learn the material other than to pass the course. This prime example of extrinsic motivation was the driving force behind almost all of my high school courses as well. I struggle to learn the material and the entire experience is unpleasant to the point that I only do what work I have to in order to get a desirable grade. To conclude, my classes that have had less of a focus on grading and actively worked to create interest gave me a much greater intrinsic motivation to learn. While classes that focused mostly on how to grade my performance resulted in my entirely extrinsic motivation to learn the material. I went to graduate colloquium meeting last Friday to listen to Dra. Antonia Darder (DAR-DARE) speak before the Unity gathering event the following day. It was a lot smaller than I expected, maybe 20 people in a small meeting room. Anyway, Dra. Darder is an internationally recognized Freirian Scholar. That is why I went. For those of you who do not know who Paulo Freire is, and you are an educator, its time to start learning about his work. He is one of the most important thinkers of this century and most people have never heard of him. Before you read further, you should at least read the first paragraph of the Wikipedia page. My own contribution was a rather elementary observation on the banking model of education during the meeting, but the rest of the conversation in our small room was nothing short of inspiring. It reminded me why I choose this profession in the first place. I want to be an agitator. Because I hate this... I've often struggled with my role as an instructional technologist because I have felt as I am merely involved in a continuance of the current educational narrative - that is, increased "performance" for less money, under increasingly rigid (and invasive) standards. It sometimes feels as if instructional technologists are non-explicitly working to kick teachers out of the role of an instructor and replace them with computers. Computers do what they are told and for less overhead, but they can only work with standardized data. This is a worrying trend.

What this meeting caused me to consider is that, if done right, the EdTech revolution in education could actually be turned into a very good thing. We don't need teachers as instructors, we need them as mentors. Computers* are far superior for delivering static instruction in bulk. The time has come to re-professionalize teachers as models for learning, as models for democracy, as learning veterans in the trenches with their students. If we need to rethink the way we think about education, it starts with power structures. As an instructional designer and technologist, I can contribute to that change. The point is that modern instructional technology has the potential to disrupt the current educational narrative in the country, to put control of education into the hands of learners; I think Freire might agree. *or other instructional technologies (e.g. video, podcasts, programmed instruction) As I delve into my old research and work to re-establish myself in the world of Academia I came across a term that everyone in my field seems to have an opinion about. Below are some of my underdeveloped thoughts. Gamificationfrom the Wiki: Gamification is the use of game thinking and game mechanics in a non-game context in order to engage users and solve problems.[1][2][3] Gamification is used in applications and processes to improve user engagement, Return on Investment, data quality, timeliness, and learning.[4] My Take My first critique is that under this definition we are seeking to simply use game thinking and game mechanics in a "non-game" context. Rather, I would argue that gamification should be focused on re-imagining "non-game" contexts as games instead of just looking to add game thinking and game mechanics. If our goal is to engage users and solve problems then simply employing these elements does not guarantee any form of success. I believe that we need to re-imagine non-game contexts as games, and then identify what types of game thinking and game mechanics are employed in order to develop off them (i.e. make implicit elements explicit). Everything is a Game In my research of game theory I came to conclude that we are normally engaged in "games." We engage in games through business, in our personal and professional relationships, through socialization, through political action, in educational pursuits, etc. Though these might not be what we traditionally categorize as "games," they very much are. To further understand how game elements are incorporated into everyday life, it helps to differentiate the two basic types of games that we play; namely zero-sum games and non-zero-sum games. In zero-sum games we operate as competitive individuals, and (ideally) as collaborative individuals in non-zero sum games - even though they (can) contain competitive elements. It can be harder to categorize gains in the latter, but recognizing gain in the former is usually straightforward.

Gamification should be focused on re-imagining non-game contexts as games. Breaking the Game I believe that when confronted with a problem humans are naturally inclined to (a) maximize gain and (b) minimize effort. These principles, when aligned to game scenarios, leads to a tendency to exploit or manipulate rules for the purpose of (a) and/or (b). The challenge for game designers, therefore, is to control or redirect these motives in a given scenarios toward productive ends (or perhaps fair ones). When the designers fail at this (and they often do) the game becomes "broken." My definition of a broken game is one which the the intended rules and outcomes of its design are subverted by its implicit flaws. Even for famed economist and MIT graduate Steven Levitt, developing games is hard: The Homework System is a Game I, like many of my peers growing up, hated homework. Like many of my peers I also occasionally cheated on homework. Don't judge me, you probably have to. Other than avoiding punishment, (a notoriously bad incentive) what was the reason to be honest about it? If my incentive is simply to get a good grade on my homework so that I pass with a "good" grade in the class, then why not cheat? Cheating becomes a calculated risk. If we don't find any intrinsic value in what we are learning, then learning it becomes an option not the object. In the case of traditional homework the grade is our primary incentive - not our participation nor our understanding of the material. We humans tend to work toward efficiency in achieving our goals, not adherence to intended protocols. If I know I can get what I want with the least possible expenditure on my part, then I will employ that methodology (e.g. cheating)! Admittedly, this "instinct" usually gets repressed because "cheating is bad," but I think we should see cheating as a way to debug our systems. It signals a time to re-examine it, realize where the design has gone wrong and redesign it! If we don't find any intrinsic value in what we are learning, then learning it becomes an option not the object. Debugging "Homework" Through Gamification I believe that human creativity will always find a way to subvert established norms for maximum gain/minimum effort (e.g., hacking culture). Therefore, we should do away with expectations of normative behavior and create "gamified" systems that are designed around incentives, rather than rigid protocols. Learning objectives should promote learning through problem solving and student autonomy (i.e., students choose when and how to participate) rather than conformity. As designers, we can assist students by providing them with navigation, productivity, and communication tools to use as they pursue an objective. A simple example: Education - a Quest

This approach eliminates:

Again, the structure already exists - we're just changing the interface; one that recognizes it, develops on it, and illustrates it. Students already "cheat" through collaboration, copying, and finding creative excuses. They talk in class and don't understand why they have to learn your material. They want to be able to "game" the system because it gives them power and freedom. So give them power and freedom; let them talk in class, let them collaborate, and let them find creative "excuses" for problems. In the end they know they have to learn the material because it's made obvious they can't advance themselves without it. They want to be able to "game" the system because it gives them power and freedom. So give them power and freedom; TL;DR (Summary)

Operating under my belief that all systems are games, I believe that "Gamification" is not about employing game elements or thinking into "non-game" environments but rather recognizing the underlying games that exist in every system and illustrating them. Designers should consider employing game thinking to design systems that are flexible, and which you know people will exploit. Attempt to channel the exploitative energy down productive and enlightening paths through game mechanics - don't get hung up on adherence to rules. Finally, use game elements to represent the mechanics for simple navigation and learner expression. If you make the incentive of the game to learn and to pursue self-betterment, and not simply to achieve some extrinsic artifact such as a grade or a badge, then you can properly "gamify" the already existing game a "non-game environment." I still have a lot of work to do on this concept, and this post was pretty disorganized, but I've been sitting on this for awhile and just wanted to get it posted. Help me develop this further by sharing any thoughts or criticisms below. |

AuthorCameron Wills is another guy with ideas and opinions. Half-baked concepts with incremental improvements go here. Archives

January 2022

Categories |

Photo from wuestenigel

RSS Feed

RSS Feed